In April 1968 Tory minister Enoch Powell delivered his infamous, racist ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech.

Three months later my father attended a trade union summer school where future Labour leader Neil Kinnock was his young tutor.

50 years on both events are are the heart of a family rift.

Can an old photograph solve the puzzle?

Enoch Powell

Jim McGachy

Neil Kinnock

Contents

A Jigsaw of Family Memories

I’d always been meaning to write and share a family history about my dad for his grandchildren …and posterity.

The catalyst was a minor disagreement with my eldest brother, Raul. Sorry, Paul. As a journalist, I don’t like to admit to my disco-lexia.

(Be fair, I mean what chance have dyslexics got with a word spelled like that?)

I deliberately blocked my own brother on Facebook after he shared an anti-immigrant meme, from the dubious “progressives” at Britain First. It’s an easy mistake to make, but wasn’t first transgression.

After all, the McGachys – in family folklore – are descended from immigrant, Irish cattle thieves.

But this old black and white photograph might hold some clues to the politics of the man we both call “dad”, sitting in the front row, far right and highlighted below in red.

‘Dad supported Enoch Powell! Paul snapped back’

Paul snapped back: “Dad supported Enoch Powell!”

It was an outrageous remark; one that demanded a rebuttal. But how? At the time of the alleged comment he was a teenager: I was a toddler!

But, here goes: This is is it.

Who, dad? Your dad? My dad? Our dad? No way, Paul!

The bloke you’re disparaging was my moral compass. He taught me everything I know; everything I believe in – from faith to football.

He made me who I am today.

To use the old punch-line; my dad… he was like a father to me!

My dad was like a Father to me

Jimmy McGachy was a typical Scottish, working-class dad. An unskilled worker, he was a committed trade unionist, a lifelong Labour voter and a devout Christian (that’s to keep the Prods reading) – describing Jesus as the first socialist.

This couldn’t be the same man, I thought. In fairness to Paul, he’s is not a binary, tribal political beast like me. But it was one of those “you what!” moments, that cuts you to the core.

It led directly to penning this blog.

‘Some families have skeletons in the cupboard; we have genocide.’

I’ve been scanning old black and white family photos for a few years now. And chronicling treasured – mainly, raucous, laugh-out-loud – McGachy anecdotes in parallel.

I’m certain every family has these: A sort of personal back catalogue of family comedy, like Fawlty Towers clips on YouTube; only the McGachy’s have a box set of shared levity.

Funerals tend to be a regular source of fun these days! They say the difference between a Scottish wedding and funeral is that there is one less drunk at a Scottish funeral.

Some families have skeletons in the cupboard; we have genocide. But that’s for another blog.

I mustn’t grumble, despite growing up in a 1970s world of global instability, political and economical turmoil, black outs and the three-day week, we laughed our way through life.

As Catholics, you could label it rosary-tinted spectacles!

Growing up was a hoot at 8 Church Street in the McGachy household. Although difficult for our parents, those times, in general, were a happy-go-lucky household where comedy and wisecracks were the norm.

Two anecdotes that immediately spring to mind. Appositely, one was at dad’s funeral. My father learned to drive late in life and wasn’t particularly adept. After his death, we discovered a stack of driving offence and fines.

St Stephen’s Church in Dalmuir was packed to the gunnels for his funeral. People standing up the aisles.

Gallus Bankies

Clydebank is a small town with a huge heart. It punches above it weight geographically and socially. It embraces a Liverpoodlian and Irish-type exceptionalism. We work, we build, we are (I nearly said “the people” there!) distinct.

On the western edge of Glasgow but just outside the city boundary, Clydebank has an obvious attitude. It’s not a suburb or a district on the outskirts of Scotland’s cultural capital – it’s soul – Glasgow.

(Edinburgh can enjoy its postcards and pretty castle views, its seat of government; but “Weegies” know they are the top dog. So does Edinburgh).

Bankies are important and signficant: building ships and sewing machines that were a huge global industry; we have a gallus-ness that demands respect. For English and foreign readers, “gallus” is a specifically West of Scotland term meaning something done with natural flair and exuberance. For football fans think; Kenny Dalglish or Jim Baxter.

Clydebank was so important that the Nazis bombed it more than Coventry! Though it was parents who lived this horror. Both my parents survived this but many thousands died and much of the town and its housing destroyed.

Consequently, Bankies enjoys a community: a friendliness and sense of belonging that pervades families, households, schools, neighbourhoods and history. If you are born a Bankie, it never leaves you.

Three-point turn

Jim – through work, through the town, through football – was well known and well respected and the family was overwhelmed with the turnout at the funeral, especially for my mum.

Six of us were designated the honour of carrying the coffin. Me and my two brothers among them. We lifted turned and walked my father’s remains out of the church to my choice of song: A rather folky, upbeat hymn called “Walk with me, oh my lord”, from my seminary days at Langbank.

It was an uplifting and fitting final journey from a church he had devotedly worshipped in for many years.

As we sat in the hearse – a mix of immediate family, the odd cousin, aunt and uncle – my brother Peter (now sadly also deceased just a few month ago) pierced the awkward silence (do all McGachys do this?) with this epic quip: “That was the best three-point turn the auld man ever did!”.

The death of a father and husband is an exceptional moment for every family. Even for those you grow up with intimately and share a common ejaculative source (all life is born out of orgasm Billy Connolly reminds us!), what words or phrases have any gravitas in these days and hours of obvious and ultimate finality?

It was a typical gallows humour to help set the for vibe the day. Not sure what the undertaker thought as we roared with idiosyncratic, McGachy laughter. Records show I’m the first McGachy to write that word along with hagiography, which this is [Editor’s note: stop showing off Chrispiny.]

After receiving the news, I packed a bag and headed for Euston for the overnight train to Glasgow. A five-hour journey I was well used; travelling up for Celtic games.

I bought the usual carry out for the train: 10 cans with one every half hour, experience taught me. Well hidden in a travel bag if you have middle class pretentions.

Despite a natural conviviality on a train trip, my instinct was don’t dine out on personal grief and subject others held in a captive carriage. So, I got quietly pissed.

As we roared through empty stations during the night, I contemplated all happy times I had made this home train journey.

On one particular trip – after a significant, lurching, tedious delay caused by problems with the overhead wires – the ticket inspector entered and sauntered through the packed, dejected carriage. He reached the table beyond me; one woman inquiring how late we would be.

“At least three cans, missus,” I interrupted enlighteningly!

‘Three cans missus!’

Another anecdote I retell still receives fits of laughter which traditionally echoed the walls of our childhood home in Radnor Park, Clydebank.

I was an editor at the staff magazine for the Department of Trade & Industry in Whitehall. I had to cover a staff awards event held at Lancaster House – a royal palace just off The Mall between Buckingham Palace and Clarence House and used for international summits hosted by the UK.

Having a chat with two other working-class Scots (from Bridgeton and Dennistoun). Together, we had made it up the greasy pole to the first rung of senior management; interlopers in the heart of The Establishment.

Sam, glancing heavenly at the ceiling, his eyes periscoping giddily around this imposing setting – dripping with gilded, gold leaf and baroque grandeur – suddenly lapsed into the vernacular and blurted out: “You know you’ve made it, when scum like us get into places like this.”

‘You know you’ve made it when scum like us get into places like this!’

Challenging Paul’s Paradox

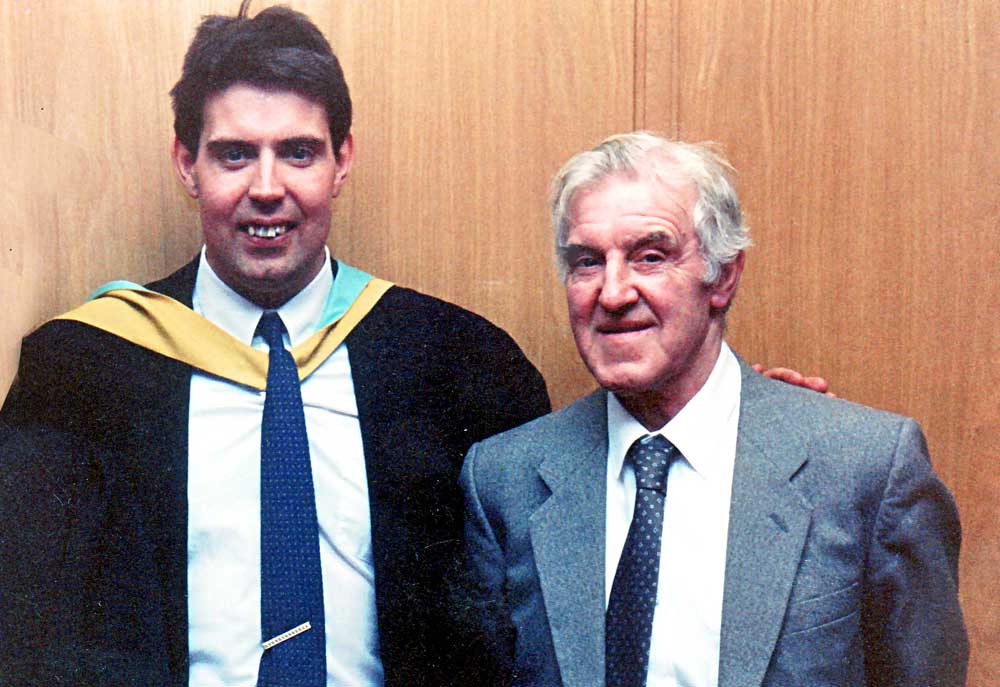

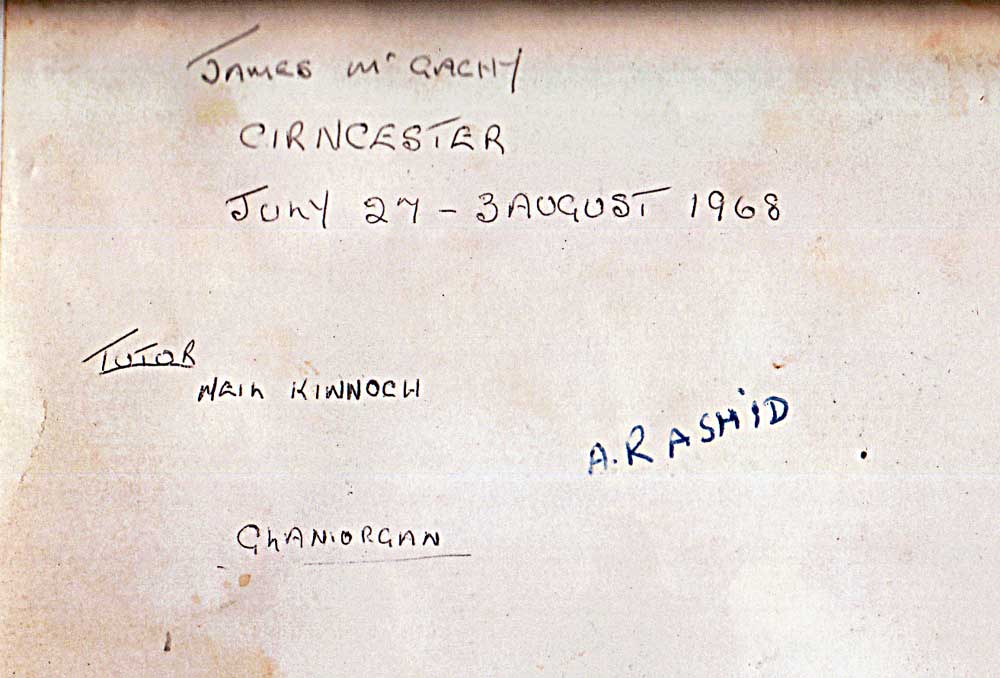

Studying the old photo of my dad with Neil Kinnock – front and back – has finally helped me unravel and tackle Paul’s disparaging paradox.

The boomer generation with parents who’ve died will relate to this. A jigsaw of recollections – from vivid memories to jumbled snippets of conversation – woven into a patchwork quilt of family; of childhood; upbringing; then as we get older trying to decipher it all with a box of random photographs and negatives.

I don’t deny my brother’s recollection or the veracity that our dad might have expressed some passing sentiment towards Powell about immigrants taking “our” jobs. But I completely reject his isolated conclusion.

Dad, like all of us – with a dogdy one-hit wonder in our 7″ single collections – was a product of his time. (For the record, mine’s is Chesney Hawkes, thanks for asking. But Up Town Top Ranking by Althea & Donna is a close second.)

Any football fan in the 70s will recall Shoot magazine. It included an regular, weekly always read column called “Focus On”. Footballers were quizzed on their favourite onfield and domestic likes and dislikes to avid fans of the format. Favourite dish was “steak and chips” or whatever.

In the early 80s in my first office job I supplied a personal humorous spoof version as a contribution for the company magazine. In context, this was the official in-house magazine distributed to around 2000 staff. Favourite colour: Johnny Mathis; Miscellaneous dislikes: Protestants and the Rythym Method.

‘Favourite colour: Johnny Mathis’

So, cards on the table Paul, we all make mistakes and say things we regret or evolve from. Don’t hate what you don’t know is the maxim. I’m sure Jesus is not too keen on crosses or carpentry as an example.

But my big brother’s assertion did lead me to explore my sense of “dad” – and a symbiotic social, political and moral upbringing.

Context and timing are important in this family narrative. Paul is older than me. When Enoch Powell made his repugnant “Rivers of Blood” speech in April 1968 my dad was 40: Paul was 13, I was six.

Only while writing this, 30 years since my father’s death, did I stumble upon this coincidence: Just three months later, in July 1968, the picture of my father was taken with a young Neil Kinnoch (sic) at a Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU) education course where the future Labour Party leader was a tutor.

All the more remarkable given my brother’s comment about our dad and Powell!

Only the good die young

James McGachy was born in Port Glasgow, Refrewshire, on 23 May 1929. He was the youngest boy of 13 children and the first adult to be buried (though a sister and two brothers died in childhood which was not uncommon in those days).

His father, Hugh McGachy – my grandad – was a shipyard riveter. Hugh McGachy was a remarkable man who spoke several languages and will be acknowledged separately with a hagiography of his own.

He travelled widely abroad in Europe despite being a man of very modest income. From conversations, my dad was in awe of his father’s achievements and outlook. I think Jim aspired to be like his father and his elder brother, Alex, his closest sibling and best friend.

He told me how the pages of my grandad’s notebooks and papers were inscribed with the letters AMDG (Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam) – a Jesuit mantra meaning “for the greater glory of god”.

I don’t know a great deal about my dad’s younger years. I know he didn’t spend a lot of time in school, ran away from home and missed much of his basic education. I also learned that he was no angel and spent time in borstal for theft of a bottle of milk (where lodging fees had to be paid for by his parents).

Football running in the Family

Eldest brother Alex McGachy was capped for Scotland at amateur level in 1939.

Alex McGachy was Jim’s closest friend and they shared a passion for football.

Jim was a decent footballer. Not as talented as his eldest brother, Alex, who was capped for Scotland at junior level, but nonetheless an accomplished, amateur full-back with a collection medals to reflect his career. I still treasure these (no takers on eBay).

Football, like his Catholic faith, was a constant part of his life…and, both passions were subsequently part of my family life too.

Dad was called up for national service in his late teens. The Second World War was over by the time he arrived in Germany in the late 1940s and thankfully he never saw active service. He told me he was a radio operator as part of the British Army on the Rhine (BAOR).

‘We teased him that he couldn’t locate Radio Clyde on the new music centre’

Years later, his kid teased him that he couldn’t locate Radio Clyde on the new music centre. He picked up a bit of the language and two words I definitely recall were fussball (football) and – at meal time – kartofeln (potatoes).

And in a nod to his time in post-war Germany, he did christen my sister Ruth with the German version of Elizabeth as a middle name.

Our Ruth Lisel quietly dropped that particular moniker.

From the photographs he apppears a socially, well-liked, outgoing, young guy. Dad was offered a football contract to stay and play in Germany but chose to return home. Perhaps romance was in the air?

Marriage and Mary McTeague

He met and was married to my mother, Mary McTeague, on Tuesday 29 June 1954. For those of you of a Catholic persuasion, St Peter & Paul’s Day, on the liturgical calendar.

Tuesday: an ususual day in any era for a wedding!

In the Catholic tradition this is a Holiday of Obligation: One of those days outside Sunday, like Christmas and Easter, when adherents must attend church mass. So, somewhat comically, as well as family, James and Mary were married in front of a congregation of giggling, local school children.

The amusing side story is that the parish priest was keen to avoid uniting the couple in holy matrimony on a Friday. As a regular, professional, religious practitioner, he didn’t want another wedding reception meal restricted to fish (as Catholics abstain from meat on a Friday in recognition of Christ’s crucifixion).

Tuesday 29th June was the only available parish date that week. Father Cush swung it with the Bishop (make sure you read that correctly: they were not swingers!) to have the marriage ceremony on St Peter and Paul’s Day.

In recognition of the wedding anniversary feast date, my two eldest brothers born in 1955 and 1956 were christened Paul and Peter.

I digress, but in later years as a left hander, asked why, with a three-syllable surname, I got a three syllable first name too. (Ruth, Pete and Paul unfazed in the margins by any fuss.)

Ever had to give your name over the phone I asked my parents exasperatedly. Ever tried signing a bank cheque.

Spare the rod, spoil the child

I believe that army service, marriage and parenthood grounded Jim McGachy; gave him a sense of purpose. In fact, they were a fiercely disciplining couple. “Spare the rod, spoil the child” is the ethos that comes to mind. It’s a pity Paul had an undiagnosed form of ADHD, or as we call them now – in more enlightened times – a right little bastard.

‘Paul was, as we call them now – in more enlightened times – a right little bastard.’

Mary was worse than Jim in the battle to discipline and I still have nightmares from being hit on the back of the legs by the wooden tongs from a twin-tub washing machine. This was the Swinging Sixties, McGachy-style.

Their parental and Catholic zeal came into its own. Both worked, both were teetotal. Mum had three jobs at one point. We weren’t rich – had no colour telly or a car (along with most) – but we wanted for nothing that mattered; food, clothes, encouragement and love. Disciplining calmed down as I grew up and the shock of being a parent mellowed.

I suspect they weren’t totally suited as a couple. A retrospective observation; not a stunning revelation.

They were happiest doing there own thing. Mum worked in silver service with the girls and dad liked football and went to bingo.

But Catholic marriage meant lifelong commitment: they made it work. I inherited the moody silences, the cold feet and the superpower of sleeping. But what a head of hair among a world of bald Facebook contemporaries: for this I’m forever in your debt, dad.

It’s bad enough being fat with the McGachy genes, but thank fuck I don’t have the bingo equlivelent of a Scottish/Irish full house: fat, bald and specky: eternal thanks Jim.

My brother Paul – while writing this – revealed that my mum’s pet name for her man was ‘curly’. Ironically most of the subsequent generations complain of a straight shock of hair: and that’s only the boys!

Religion and Activism

But the time I was born in 1962 my father would have been in his early 30s. I was something of “rainbow child” after a younger brother, Stephen, died suddenly.

He worked in the Royal Ordnance Factory. The Bishopton site was the biggest MoD munitions operation in the UK with about 20,000 workers.

He then joined Babcox & Wilcox in Dalmuir, Clydebank. The US engineering company was a world leader in steam boilers and generators which it patented worldwide. Later it diversified into other production areas, such as crane manufacturing.

Dalmuir on film

Clydebank was a worldwide hub of heavy industry which included John Brown’s shipbuilders, Singers sewing machines and other large manufacturers.

The button links to one of a series of 20 films made for Babcocks and Wilcox in the post-war era.

Crucially, in addition to his day job as a crane driver, my dad took an active interest in the trade union and was elected a stop steward with the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU).

It’s patently clear to me that his religion, his activism, his desire for self-improvement – perhaps to make up for missed schooling and subconsciously to measure up to his father (along with a desire to make the world a better place) – all crystalised up in his union activities and political views. I was destined to follow in his footsteps.

Meanwhile, his religious devotion continued. He once confided to me that he was overpaid and asked the priest in confession for advice. He duly informed his superiors and repaid the extra money. His Catholicism was not merely a Sunday obligation to attend mass but an active, positive, living faith.

I recall another conversation in which he admitted that he would live his life differently if he wasn’t committed to a reward in the next life. Mass wasn’t just for Sundays. On holiday in Nairn, we went to church every day and I recall going to mass twice at Christmas and Easter in addition to Novenas and all-night vigils. Despite being a committed Catholic in those days, it would be fair to say the Holy Week was not my favourite time of the year.

So common was this combination of Irish, immigrant, Catholic, socialist activism that, in later years, the Labour Party domination of Scottish town halls was described as the Murphioso. Jim revelled in the fact that the adjective “catholic” – with a lower case “c” – also meant universal.

The Holy Trinity

Faith, family and football; these were Jim’s McGachy’s overlapping playing fields. He had been going to games at Celtic Park regularly since the 1950s. My dad was a member of the Clydebank District Celtic Supporters Club.

My first outing to this eathly “Paradise” was a win against St Johnstone at Parkhead in 1969. It was a great time to be a Celtic fan in the midst of a record-breaking nine consecutive league titles, regular trips to Hampden for cup finals and huge European games covered in a separate blog.

Pointedly, my father refused to take me to a Celtic versus Rangers game. He vocally objected to the bigotry and I know he wanted to shield me from the sectarianism that surrounds the fixture. But I was already learning the traditional [read political] Irish songbook.

I was 16 before I sampled an “Old Firm” game. But an enduring memory was going to games with dad and uncle Alex. I still have many match programmes, ticket stubs which are treasured childhood souvenirs from this era.

Dad pictured with the Scottish League Cup trophy

Chris with his hand on the Scottish FA Cup in 1969

When neighbours, an elderly protestant couple, were shamed in the court pages of the Clydebank Post for shoplifting, he forbade us talking about it or poking fun; we were not to know the circumstances or possible poverty. This was the moral stature of the man I’m proud to call my dad.

‘This was the moral stature of the man I’m proud to call my dad’

We dared not defy him; even though their (proddy) dog bit me! I still have the scar! It was years before I realised dogs are non-denominational.

Looking back, I admire his opportunism and negotiating skills. My dad used his connection with the supporter’s club bus driver, Davie Syme, to hire him on quiet Tuesday nights to run a small Catholic group to the south side of Glasgow for a Novena in St Francis Church in Gorbals, run by Franciscan monks. Jim was a generous man when it came to charity and the foreign missions. Maybe punching above your weight is a McGachy trait.

I recall having a £5 note pinned into a zipped blazer pocket to give to the “black babies” as the school charity collection was dreadfully known in less enlightened and more colonial times.

We clashed over separate Catholic schooling which I thought was divisive while he argued that Catholics had been neglected and forced to set up their own schools to defend their beliefs and faith; and that they were worth keeping for that reason. But it was an early example of our religious and political divergence.

Nevertheless, he wasn’t averse to criticising the clergy where he saw theological aberration. He had little time for one particular local priest for spending more time badgering the congregation to fill in covenant (tax relief) forms to raise money for a new church hall than he spent delivering a sermon. Yes, Jimmy would certainly have been on the picket line with Jesus expelling the money lenders from the temple.

The Road away from Home

I moved to London in 1980 as an 18-year old. Though I had trained to be a priest, by 24, I had stopped attending mass and decided that I had to tell my dad that I had outgrown god, even though they were only visiting over one weekend. It was just too important for me to duck the conversation.

After all, he had stopped visiting one brother when they didn’t send their child to a catholic school, as (he saw it) they had promised with their marriage and baptism vows.

My dad died in suddenly of a heart attack in 1990 aged 60. He had been visiting me in London to attend my graduation ceremony and I saw him and my mum off at Euston the day before he died. It was and still is a total shock. Never getting the chance to say a proper goodbye. Writing his story is a great way to pay my respects and tell you all how much I respect and love him.

Solving the racist riddle

So, all I have left now are the memories, family recollections and the faded photos. This bright coloured folder had kicked around the family home for years.

Battered and now ripped, it came into my possession (again) stuffed with other unconnected photos of grandparents in addition to a jumble of birth and death certificates and old wedding invitations. The student and tutor photograph of dad and Neil Kinnock from 1968 was inside but no longer signficantly connected.

That was until recently. The enforced Coronavirus lockdown has allowed me time to piece together the jigsaw and gave me the lightbulb moment of revelation.

Sensing Neil Kinnock might have time on his hands during lockdown, I emailed him a copy of the photograph to ask if he had any memories of his days as a tutor on the course; and the prevailing mood surrounding Powell’s speech in particular, and working-class attitudes more generally.

I wasn’t expecting him to remember my dad personally, but just to add some colour, context and ‘political stardust’ to the story. (Even socialists need celebrity!)

Neil didn’t disappoint. I sent the email first thing early on a Saturday morning and he replied in detail by 2pm in the afternoon. We have continued our converstation of a series of emails.

Neil Kinnock’s recollections

“Dear Chris, your letter and the class photo brought back great memories,” the ex-Labour leader, now Lord Kinnock, said.

“Powell’s infamous Rivers of Blood speech had a huge impact, mainly because it appeared to give respectability to feelings of resentment – stoked by right-wing newspapers – that were harboured by large numbers of people of all classes, including union members.

“In fact, it was TGWU members – London dockers – who downed tools and marched to Parliament in support of Powellism, as it was called.

“Fortunately, TUC unions and the Labour Party were active and long-established anti-racists and stood strongly against Powell and his followers. To his credit, Tory Leader Ted Heath, instantly sacked Powell from the Conservative Front Bench in April 1968.”

The former Labour leader admitted that it was not uncommon for working-class, union members to reflect the prejudices of the time.

‘It was not uncommon for working-class, union members to reflect the prejudices of the time.’

“The summer school classes had a wide mix of people from all industries and services. And the exchange of experiences and challenges between a female, West Wales bus conductor, a Wolverhampton forge fitter and a Geordie lighthouse keeper, was as valuable as it was fascinating to both to tutors and students.

“And when you threw in some Scouse dockers or Cockney cab drivers the mixture was very funny too.”

I’m sure dad, who loved a joke and good time, would have been in his element at the week-long course. Neil explained that apart from the academic learning, which dad would also have immersed himself in; the College was more a mix of public school and holiday camp.

For a man who worked a manual job, much of it on night shift in heavy industry, this week, I imagine. would have been a welcome break from family and domestic cares.

Neil explained that the College was set in beautiful parkland a few miles outside Cirencester in the Gloucestershire countryside and fairly accessible for most of England and Wales, although as a Scot he admitted, my dad would have had a long journey either end.

He said that classes finished at 4pm each day and the sports fields and equipment were well used for soccer and cricket. “The beer at the College bar, opened between 6 and 10.30pm, was good and cheap,” he said.

Neil had attended the what is now Cardiff University, where he graduated with a degree in Industrial Relations and History in 1965 and a year later a postgraduate diploma in education.

He then joined the Worker’s Educational Association (WEA) in 1966 and worked as a tutor on the trade union summer school courses where my father crossed paths with him.

Recalling his teaching days before he was elected the Labour MP for Bedwellty in South Wales in the 1970 general election he said:

“The TGWU used the Royal Agricultural College at Cirencester for Summer Schools for union reps for about 15 years from the early 1960s. In the main because it was big enough to accommodate about 450 residential students for a week-long course held in July and August and was cheap in comparison to hiring a hotel.

“As tutors were paid £25 a week and travel expenses and most of us did two weeks a year. And from a personal point of view, I could nip home on a Friday night to see my wife Glenys in South Wales.

“The food was lousy; but a generation of wartime and National Service men like your dad didn’t worry much about that and the women just ignored it.”

Neil said that classes consisted of up to 20 students led mostly by WEA industrial tutors like himself. Others teachers came from the adult education departments of universities.

“We taught Communication consisting of compiling written and oral reports according to a formula developed by the Royal Canadian Air Force, bargaining techniques and the history and philosophy of British trade unionism.

Fertile political recruiting ground

“Obviously, formal and informal discussions ranged very widely. I made no secret of my efforts to recruit students to the Labour Party and also encouraged several who I thought could benefit further education.”

‘I made no secret of my efforts to recruit students to the Labour Party.’

“Those who showed strong promise in these courses were encouraged to undertake training for full-time officer posts. But most, naturally, returned to their positions as better trained and more confident branch officials, shop stewards and convenors.”

He revealed that one former Cirencester student was a Jamaican-born, Nottingham bus drive called Bill Morris. 18 years later Bill became General Secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union that my father was a shop steward in.

Having personally benefitted from professional and personal development courses as both a trade union rep and a career civil servant, I am convinced that the 1968 TGWU summer school was an important milestone, if not life-changing event for my dad.

It gave a working-class man with patchy education the confidence and context for to develop intellectually and politically as a solid socialist. And for anyone who has enjoyed the benefit of professional training, it gives you confidence and maturity as human being. I know that’s how I feel.

I learned a lifelong lesson observing at the middle-class and public school work colleagues in Whitehall. From an early age, people from these backgrounds take career progression and success as a norm. Conversely, working-class kids feel awkard about promoting their abilities and their worth.

These guys (look at ‘Bullshit Boris’ as a case in point) are adept at crowing how good they are; if you are working class you need to shout about your abilities; no on else will do it for you. And I’ve seen some piss-poor, priveleged professionals in my time.

The current Labour Party, the only real representative of the working class, is dominated by middle-class careerists, who see it as a cushy job for life. The devastation of the union movement means the party has lost a crucial connection with working-class communities.

I went to university as a mature student and benefitted from that immeasurably. But the Labour Party has to reconnect and reflect it’s natural demographic, particularly in Scotland and Wales and the Brexit constituencies of England.

For my dad’s story, the bottom line is that – even if you don’t become an MP or union leader – attendance as a union rep at the school was an important step for my father up the ladder of inward confidence, outward ability …and maturity.

Enduring childhood memory

The deeply personal aspect of this entire story (my dad, the group photo and my brother’s allegation) is that I have a vivid recollection of bumping into my dad unexpectedly outside the house a few streets away on the very night he returned from the summer school. I was a mere six years old.

It’s etched in my memory. It was a sunny summer evening around 6.30. I thought it was a Sunday but the folder dates tell me it was a Saturday.

I was out playing when I ran into him on the corner of Granville Street and West Thompson Street – for locals who know the area.

‘It was the longest time my father had ever been away.’

I instinctivly ran into his arms and he dropped his case, picked me up and hugged me. He had been away for a whole week as the folder shows. It was the longest time my father had ever been away from home in my entire life. We had missed each other and walked home together, hand-in-hand to Church Street.

It’s only since his sudden death and the scanning of the old images I’ve been able to connect this precious, childhood memory.

As I now hurtle towards 60 myself – the age my dad died – it remains an enduring, joyful moment. Speaking to Neil Kinnock, I now have a bit of context to tell the story for family posterity.

Reading between the lines

But here’s the thing; there is a little bit more to dad’s story in the photograph with Neil Kinnock. Sandwiched in between my dad and Mr Kinnock is a younger Asian man. He is perceptibly the only black and foreign student on the course.

It was another clue hidden in plain sight.

I reached for my notes. Ephemeral recollections casually collected over the last 30 years since that dark February night on the train to Glasgow.

Random thoughts written in diaries, on scrap paper and notebooks that survived various computer upgrades. Still uncollated and haphazard but now typed: searchable; findable.

Sure enough, dated 2018 but realistically written earlier; it was serendipity: Like opening a random drawer and finding the thing you were looking for right in front of you.

Growing up, my dad mentioned a man he had met from Bangladesh. Bear in mind, at this point, I had never met anyone from Partick or visited Edinburgh.

In current conversation, Paul admits he remembers this story and the connection with Abdul too.

‘the new mate had arranged for flowers to be delivered to our home address.’

He had struck up a strong friendship enough for a 10-year old to recall the conversation. So much so, that on his return to his homeland, the new mate had arranged for flowers to be delivered to our home address. As usual, religion plays a part in why I remember this.

I sent a follow up email to Mr Kinnock to ask him if overseas students, like the man seated next, to him attended the summer school. Only this time I included the detail about my brother’s suggestion that my dad was a closet racist. Again, within a matter of hours, Neil came back to me.

Progressive Conversations

Neil said: “Thanks for your letter and interesting questions. My memories of 52 years ago are a bit dim, but here goes.

“For some students it was the first time they had ever encountered ‘progressive’ arguments.

“As you can imagine, residual racism and casual sexism were challenged.”

“It might have been that your dad arrived with what were then conventional views, mildly held; and he left with strongly held anti-racist attitudes which had wider political implications.

“That certainly happened to some and I observed – I’m happy to say – that change in thinking among several of my adult students in my daily work in South Wales.

“I only remember one occasion where the [racist] talk boiled over and us tutors confronted a Northern Ireland defence worker about his reactionary views.

“The peace was restored and, in the days following, he established a relationship with black trade union member Bill Morris based on their shared love of cricket.

Bill was a fine bowler and batsman and, notably, the Northern Irishman started expressing changed opinions.

“By the 1969 Summer School my fellow tutors and I were very pleased by the fact that the issues of race and immigration had no particular prevalence among students.”

Significantly, in my dad’s story, Mr Kinnock confirmed that the union training did indeed include overseas students attending the summer school.

‘union training did indeed include overseas students’

“Usually they came from countries where workers’ organisations, trade unions and political activists who faced repressive governments.

“Although by the late 1960s British trade unions were starting to see non-white, first-generation immigrants elected as shop stewards.”

In a subsequent email, I interrogated Neil about the picture and the fact that my dad is one of the few in shirt, tie and suit. Looking to measure up and make an impression, I speculated.

Neil said: “The fact that your dad wore a suit and tie to the school was not at all unusual. Working class men had few clothes.

“I had one suit – my wedding suit – when I got to Parliament in 1970 and my dad had two, including one for funerals and one for an occasion like this photo where it was usual to dress in your best.

“You’ll notice from the photo that all students had shiny shoes and there were no trainers. That, too, was usual and derived mainly from the convention of being ‘well turned out’.

“As my dad (ex-collier and, after 27 years underground and being disabled, a steelworker) told me: ‘Remember Neil, MP stands for a man of principle as well as Member of Parliament.

“‘Never let yourself down – you can always be clean and put a crease in your trousers and a shine on your shoes’.”

Friendship Flowers and Flashbacks

I told Neil I had a vivid childhood memory of a huge bouquet of flowers being delivered to our house.

In those days the only time we got a knock on the door from someone we didn’t know, was the police (with a warrant for Paul or Peter, generally). To recieve a door delivery was unusual, to recieve flowers was highly unusual; and to receive flowers for your dad rather than your mum was unique.

Another reason it sticks in the memory is that – rather than display them at home to wilt – my dad eagerly donated the bouquet to the local parish church and was thrilled to see them adorning the altar at mass the following Sunday. It’s no fluke I remember this.

Neil responded: “It is very likely that Abdul did since he and your Dad clearly struck up a good friendship and it would be quite usual, in those days, for a Bengali like him to send an affectionate token of that kind.”

Until that point I had read but never studied the reverse of the image. I scanned it and blew it up on the screen. It was just like dad to write on the back of a photograph. No point in having the picture if you don’t know anything about it, was his perspective.

I have many examples to highlight dad’s archivist instincts. He painstakingly went through old football pictures with his brother Alex, writing down – not just the names of the players – but even the management and committee members pictured. A man to my own organised heart. He taught me by example.

But the clincher in this long-winded but personally, cathartic lifestory is that the image reveals that my dad hasn’t marked the name of his new-found, foreign friend; the letters and ink colour are noticeably different.

My father doesn’t dot the “i”s, his “a”s are rounded with a top stem. It’s not my father’s handwriting; it’s Abdul Rashid’s.

‘It’s not my father’s handwriting: it’s Abdul Rashid’s.’

Now, I know this isn’t much of detective story for others, but this was the ‘Agatha Christie’ moment for me in my response to my brother about my father’s politics.

The fact that my father has asked for Abdul’s name or Abdul has asked to keep in touch adds huge significance to this 50-year-old photograph and my father’s legacy.

Suddenly it all makes sense to me.

At the crossroads of Clydebank and Chittagong

Out of all the people on the week-long course, my father had met a new friend; he had formed an instant and instictive friendship with this man who has travelled thousands of miles from away home, out of his comfort zone and – among strangers.

It’s an attitude and approach I still adopt to this day! I’m magnetically attracted to the outsiders.

Yet despite being a different nationality, a differerent race, a different colour, a different creed; in a spirit of solidarity, my dad connected with a fellow worker, a fellow union member and a fellow human being.

I don’t think it’s coincidence that they are sitting immediately next to each other, smiling contently. There is almost a romanticism captured in the 50-year old black and white image that expresses this story.

These two men have bonded politically and personally. Abdul Rashid and Jim McGachy have a shared story of upbringing, of poverty, of working hard, of striving to succeed, of punching above their weight, of representing and advocating for others worse off than themselves. It’s what trade unionism and socialism are all about.

Collectively, the entire story – Powell’s odious speech, dad’s attendance at union summer school, the friendship with Abdul, the flowers, my dad’s fear that his newfound friend had died – all add up to something diametrically, cognitively and emotionally different to the picture my brother Paul had painted.

Nearing sixty rather than six has allowed me pierce the fog of memory and restore my father’s political “last will and testament”; at least in my mind.

Colliding paths in a volatile world

Following the TGWU school in 1968, Adbul Rashid would have returned to a homeland in East Pakistan which was in huge, international, political turmoil with Bengalis seeking greater autonomy and independence. West Pakistan’s military waged genocide with up to three million people being killed.

The contact between Abdul and my father dried up. He told me he feared that his friend and fellow trade unionist, Abdul Rashid, had died in the war which led to the state of Bangladesh being set up in 1971.

I was too young to appreciate these violent and turbulent time till now. I fully intend that the next chapter in the story will be to track down the Abdul’s descended family to find out what happened and share the story of their friendship. (I’ve been in touch with the TGWU to see if attendence records exist)

Back in Britain at the same, the country was in political and economic upheaval with largescale industrial decline causing closures and unemployment.

As Branch Secretary of the T&G my dad would have been heavily involved in discussions to try and save the Dalmuir factory.

It was closed in 1969 effectively throwing my dad and many like him on the economic scrapheap with a young family of four to keep. These must have been desperately worrying times for Jim and Mary.

Poverty porn pioneers!

By 1972, my dad was aged 43 in an area of mass unemployment. I’m sure his union involvement had led to him being contacted by the TV company. Our family featured in a documentary about unemployment. I was 10 years old and recall being a bit of a celebrity at school because of it.

Unemployment in Clydebank

A current affairs programme about the bad unemployment situation in Clydebank during the 1970s

As this was in the days before video recorders (remember them) we never had a copy of it. Years later, one of my brother Paul’s mates spotted his face in a TV clip during a 1970s retrospective about Scotland.

Following a little bit of research and a few calls we were able to get a copy of the movie from the Scottish Film Archive. Strange to see dad cooking in the kitchen in glorious technicolour (well, mustard), magically brought back to life.

By the late 70s, dad had ended his long tradition of going to Celtic games. The sale of Kenny Dalglish and the biscuit tin-mentality meant he stopped attending regularly.

Indeed, our last game together was a dreadful December home defeat to Dunfermline in 1989. It broke my heart in retrospect. All the great players, games and victories this man had witnessed. 1967, nine-in-row, cup finals; and the success and lifelong tradition he introduced to. It was a cruel curtain.

He had always told me that Celtic had to beat 12 men as the referees were biased towards a different Glasgow club. It all ended well, Jimmy, the Rangers died cheating and Celtic did nine in a row again. I know how happy he would be in 2020, the year on his 90th birthday.

You can’t be a Catholic Conservative

Neil Kinnock became leader of the Labour Party in 1983. I actually voted for him and Roy Hattersley when I joined the Party in the early 80s in Kensington where my Civil Service hostel was: the smallest Labour vote in the UK.

He was unfortunate to lead the party during one of the longest periods in opposition but faced down my father’s nemisis, Margaret Thatcher, across the Commons despatch box.

Football, religion and politics were a constant topic of conversation growing up in the McGachy household. During one discussion, on the monarchy my brother Peter inquired: “Was that the King who abducted?” (meaning abdicated).

As you can imagine he despised the Tories and Margaret Thatcher. Entering Downing Street in 1979 as Prime Minister, she quoted the words of St Francis of Assisi to the waiting TV cameras.

“Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope.”

I remember the rage my father felt. As a long time admirer and supporter of the Franciscan order he was apoplectic that a Tory politician could use the words of a dearly adored Catholic saint.

‘I remember the rage my father felt.’

He held a particular loathing for Tory minister Norman St John Stevas (born the week before my dad coincidently) who from time to time appeared on news screens as a Conservative spokesman on Catholic and religious matters. For Jimmy, he could not reconcile how any Catholic could be a Tory; the two ideas were fundamentally incompatible.

Thatcher enters No 10 with St Francis quote in 1979

Norman St John Stevas

Neil Kinnock gave a famous speech in which he asked why he had been the first in generations to get the opportunity to go to university. Similarly, I was the first and only one in our household to get a degree. It came a generation too late for Jim. But no doubt his upbringing got me there.

There are lots of physical memories: the football programmes, the photographs and the union branch administration stamps (my father had beautiful handwriting and a distictive signature).

But perhaps it is the political and religious grounding that has been my father’s greatest legacy. Without his direction and encouragement, I might never have made it to university and the fulfilling career and life that it led me to.

London Lights and Dark Days

Growing up in London I mixed with in new world: a world of foreigners, gay people, black people, sihks, protestants, communists, alcoholics, and

white-collar workers. (but mainly middle-class alcoholics).

I took a few of them home to Clydebank. We talked football, politics and everything in between.

I can honestly say my parents welcomed anyone – of any colour, any creed – with the honest, working-class hospitality that Scots are world-famous for.

I often went home to watch Celtic games over a weekend. Glasgow Celtic have an important part of this political and religious family story.

A football side formed by an Irish priest to help feed the poor Catholic

immigrants of Glasgow. For most in this tradition, the club has become a symbol of their identity and their politics; and its success is the triumph of the socio-economic underdog – against all the odds and forces against them.

It’s a powerful narrative which Jim McGachy embodies like generations of Catholics, socialists and Celtic supporters before and since his untimely

death.

Support for Palestine or unfashionable causes would not be lost on him. It’s another the reason I don’t think he could be a racist. I know him too

well.

My brother Paul was married by 1977 when he was 21. I started work in London on my 18th birthday. Within two years I became active in the trade union and was elected first and Branch Secretary and then Chairman as well as joining the Labour Party.

In between letters to my mum and dad I went home regularly for football games. As Thatcher wreaked havoc and Neil Kinnock faced her across the Commons, I spoke to my dad constantly about politics during these dark days to be from a working-class community.

Together, we continued to discuss and develop as adults and socialists. The

one certainty I have about my dad was and is his human decency. From foreigners and the Protestant shoplifters (great name for a band!) to money-minded clergy, Jim McGachy showed consistency in his thoughts and action.

It confirms my personal conviction that my dad, Paul’s dad, our dad, was no supporter of Powell or racism.

As an articulate, adult son – through intensely political times witnessing

that consistency and the story laid out here – it confirms my personal conviction that my dad, Paul’s dad, our dad, was no supporter of Powell or racism.

Enoch Powell once said that all political lives, unless they are cut off in

midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure. Powell ended up on the wrong side of history as an Ulster Unionist MP in crackhouse of UK politics. He certainly fulfilled his own prediction.

Dad would not be surprised to find out that the Rangers, after a decade of financial cheating, died in 2012. Dad, I’m still toasting the “Banter Years”.

I suppose we all have different relationships with our parents and siblings. I’m a middle child and that gives the parents time to work out what they’re doing, right or wrong. Younger kids – as their parents age and mature tactically – get an easier ride.

There is a wonderful old gag. I was brought up as an only child: which really pissed off my brothers and sister. Main protagonist in this story, Paul, was the first born was always my mother’s favourite.

I learned from all of them. I remember my brother Peter coming in from the nightshift in the shipyards where he worked at the same time as Billy Connolly. Both welders and comedians.

He was black from head to toe in his work boilersuit. I thought to myself. I don’t know what I want to do; but I don’t want to do that. I’d better stick in a school. Incidently, my dad earned £7 a week, Peter was on £15.

It’s a tremendous privilege to say how proud of my father I am and what he taught me; what he made me.

I’m not my dad, Jim McGachy; but I recognize the DNA.

James McGachy, born 23 May 1929, died 15 February 1990, aged 60.

Any resemblance to real (fat) persons or other real-life entities is purely coincidental.

This story is dedicated to the memory

of Stephen McGachy

I want to dedicate this to my big brother Stephen. He died suddenly one week before his first birthday in September 1960 before I was born.

It was a traumatic, unfathomable loss for Jim and Mary and must have tested their faith to the limit.

Stephen’s death would also have had an influence in the life outlook of a my dad, a young father of 30. I can only speculate that it made him more determined as person.

As an adult my mum revealed to me that, after Stephen’s death, she found herself looking in other mother’s prams to check if it was possibly her own son; and this was all a divine test of her faith – a nightmare she might hopefully awake from.

I cannot imagine how either – both devout Catholic believers – carried on as normal parents or human beings. I admire their pragmatism but I no longer believe in their “god”, their faith or his mysterious ways.

My elder brothers Paul and Peter, aged five and four, grew up and played their younger brother and remember him. But it would crass for me to claim any suffering. Though I do often wonder what the dynamic would have been had he lived.

My puny loss is being piggy in the middle; with the nearest brother eight years older and my sister five years younger.

Stephen – probably my best mate – is the missing link. More than likely an absolute comedian, maybe above average singer, definitely liked a bevvy or two – a bloke just his wee brother Chris.

As a family, as brothers and sister, we rarely took/take the opportunity acknowledge the brother we could have grown up with.

So, Stephen, this story is for you. Your dad was good man, your mum was a diamond; they would have made you the same.

Stephen Hugh McGachy born 22 October 1959, died 15 October 1960

Dad Jim with Stepher McGachy as a baby and older brother Paul (left) and Peter (far right). The only far right in this story!

Stephen Hugh McGachy born 22 October 1959, died 15 October 1960

Chris McGachy, May 2020.

Globe Trotsky is a retirement travel, lifestyle and photography blog for the independent, budget traveller. A sideways look at travel in a tshirt. Visit www.globetrotsky.com to join the travel and tshirt tribe.

15 Comments

Fra mcgachy · at

Great read Chris. We have defo had the same upbringing our fathers were born in 1929 so they’re from the same era . Family faith and Celtic. I thank god every day for that upbringing

john reilly · at

Incredibly detailed and thoughtful portrayal of life growing up in the McGachy household!-Who would have known there was so much going on in the house barely 20 yards from ours!

odonnelljack52 · at

we are the same age. My mum also lost her first born. Funnily enough I was writing stuff too about my da. https://www.abctales.com/story/celticman/old-geezer

admin · at

Thanks Jack. I can’t believe how many similarities in a father’s story. Made me chuckle. I’ll leave a comment over on yours.

Timothy Wright · at

Hi Chris.I found this blog about yout father very interesting. I must say I am slightly surprised he had a particular dislike for Norman St.John Stevas as – whatever you think of his party – he was the most liberal of Tories, strongly opposed to Powell and was the first cabinet minister to be sacked ( as Leader of the House ) by Mrs.Thatcher in January 1981. He was also gay ( but not openly ) at a time when homophobia was common in the Tory party and probably not unknown in Labour, either. Now there are openly gay / lesbian senior politicians of both main parties

(eg. Ben Bradshaw, Chris Smith, Angela Eagle for Labour; Justine Greenning, Alan Duncan, Nick Gibb for Tories) That’s progress !

On another point I was impressed to read about your praise for the radical American nun, inspired by her faith to do good, given your hostility to all religions,as expressed on Facebook to me in March ( and at other times ). I declare an interest; I am a practising Christian ( liberal Anglican) and have witnessed first-hand, as much as any atheist, the harm that extreme, fundamentalist Christianity can do. However this is not the whole story, as Desmond Tutu, Martin Luther KIng and many others, lesser well-known, can prove. Please don’t judge us as all the same as the fanatical idiots. I was a regular churchgoer for all of my 30 years in London ( and still am ) and got to know some inspiring believers who genuinely helped those in need without ‘ ramming God down their throat’.

Best wishes, Tim Wright

admin · at

Thanks for taking the time to read the blog, TIm.

I must admit it wasn’t until I was writing my dad’s story that I looked up Norman St John Stevas again recently. Primarily as I was looking to use an image of him in the blog as he featured so centrally in the memory of my dad’s story.

Agreed, he certainly was a colourful if conflicted character; a liberal in favour of decriminalising homosexuality but a reactionary against a women’s right to abortion. Should we surmise that liberal values were okay for him personally but not appropriate in other aspects of Catholic faith! A bit hypocritical don’t you think?

There has been real progress in lots of spheres and social attitudes but it’s not the Church or religion that has been in the vanguard of this progress. Without being unkind, I view the Church of England as one of those quaint little branches of religion; set up so that the monarch could undermine his solemn vow of marriage for a leg over with his new fling.

It’s fascinating to witness the contortions that the Anglican Communion gets itself into over the ordination of women, same sex marriage and homosexuality while trying to keep it’s African bigots from schism.

Whether its Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, the Jewish proclivity to mutilate babies newborn males or the Islamic subjugation of women; I believe these and the teaching of these belief systems are fundamentalism, even child abuse.

We have had progress in lifestyle and attitudes but in spite of religion, though I accept your point that there have been many decent and well meaning people who have done great things in its name.

But what good is a Mother Teresa if she doesn’t tackle the reasons for starvation and poverty! I’m reminded of the words of Brazilian Archbishop, Hélder Câmara. “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist.”

I’m glad you found your way onto the Corita Kent blog. But again one should note that she also became an apostate and left the Catholic religion. While the less fun loving liberal Anglicans, like Ann Widdecombe go in the other direction.

And one only has to look to the ISIS of Anglicanism in Northen Ireland, to see the brutal underbelly of religious bigotry. Anglican is little tea-party for middle England. It’s not really a religion, with less than 750k attending regular services; it’s more of day out. Ikea has 60 million UK customers as a comparison.

My atheism may come across as aggressive but I have the same passion as the good Samaritans you mention in your notes. I want to help people and make the world a better place. But this world, not a non-existent next one. There is no polite way to tell people who believe in god that they are devoting their lives to a folly.

I was meant to be in the US before Coronavirus. But postponing till at least next year. So I’m busy reading about all the nut-case Christian offshoots in the USA. I believe it started with the Puritans; who thought the Anglicans weren’t taking the Reformation seriously enough.

Nothing personal Tim, I’m always happy to have a discussion about religion, in fact I really find it quite fascinating have come from a devout unbringing and outgrown it. I find the process an unburdening. Next time you are down in London, let’s meet up and have a drink. Thanks for reading the blog. Chris

tim64w · at

Hi Chris, very interesting story about your dad . (NB Powell was actually a shadow minister in April 1968 ). I’m a bit surprised he had a particular dislike for Norman StJohn Stevas; he was a very liberal Tory ( anti-Powell ), also gay ( but not openly ) when homophobia was rife in the Tory party and probably existed in Labour. Now there are openly gay/lesbian senior ministers of both major parties ( Ben Bradshaw, Justine Greening, Chris Smith, Alan Duncan ). That’s progress !

Timothy Wright · at

Thanks for your reply, Chris and sorry about repeating myself in my second post I wasn’t sure the first one had got through. David Godfrey, Andy Shall and many of my personal friends share your unbellief and are obviously decent people, I don’t take it personally; my faith is very important to me but I never have and never will impose my beliefs on others. Some ‘bible bashers’ woud not regard me as a real Christian !

I know you, like me, knew and liked Caryle David (RIP), I sometimes used to go to church services followed by a drink/meal with Carlyle, his brother is a non-stipendary priest and he rang me to say thanks for a letter I wrote him. It’s so sad; I visited him in early February, he died 1 month later. William ( his brother ) told me there will be a memorial service later in the year; if I will find out the details I will let you know.

PS Ann Widdecome was never liberal as an Anglican !

PPS Do you not find a slight conflict in being a st

aunch athesit and supporting a Catholic football team ? I ask this out ot curiosity not cycnicism.

admin · at

Hi Tim, I suppose my main interest is to at least see atheism as a mainstream commentary, rather than having the reverend on our screens every time there is a tragedy. Although I would like to see an end to religious schooling, I would accept a secular rather than atheist polity.

Funny enough, I always felt at home with the politics at Celtic. Not sure if you know that both Jock Stein, Kenny Dalglish and a host of other players were actually Protestants. When I was growing up we had a wonderful player named Paul Wilson, whose mother was Bangladeshi. He was a great talent and the latest in a line of black and ethic players to play in the hoops. https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/wnmgnw/remembering-gil-heron-the-first-black-footballer-to-play-for-celtic

We were set up by an Irish Catholic priest to raise funds to feed the poor of Glasgow. So its always had socialist and charitatable ideals. You will probably have heard of our support for the Palestinian cause. As a club founded by immigrants, solidarity is not lost on the Celtic support.

During the recent statue controversy, a section of the Celtic support changed the slave owner street names in Glasgow in solidarity the call for equal treatment of black people. https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/scottish-news/change-gonna-come-green-brigade-22162274

I acutally revel in being the socio economic underdogs against the Establishment club. I’m now a shareholder. My football team fits my politics like a glove.

John Pugh · at

Hi Chris, A great insight into your family history as well as a heartfelt tribute to your dad. My dad, a contemporary of your uncle Bill (Rosaleen’s dad), remembered your Granda acting as an interpreter for sailors at the Rothesay Dock.

admin · at

Thanks John, much appreciated comment. I spent a bit of time with Bill in London…and as the oldest referee in Scotland, there is a story worth writing!

TheBabelFish · at

Hi Chris, Derek here. I really enjoyed reading this, and realised we have much more in common than I ever knew back in the day. Apart from football. We went different ways on that one, but for interesting reasons. One thing I’m sure you’d agree with – you don’t change. That decision, once made, is for life, otherwise what’s the point? And I completely understand and respect your loyalty to your choice. especially as it was such a strong bond with your father.

My dad wasn’t particularly bothered with football. He was a rugby man, had played fairly seriously in his youth. And he was an atheist, so he wasn’t drawn to a team for that reason. When I went to school, everyone supported Rangers, so I sort of did too by default, but with no particular enthusiasm. But as I came to better understand the Scottish sectarian situation I became increasingly uncomfortable with that notional support, and I voiced that disquiet with my dad.

He said well, why not support your local team then? I found that suggestion sufficiently intriguing that I decided to take myself along to a Bankies match shortly after. As it happened I was just the right age to watch a certain young winger – Cooper, D – becoming one of the special ones right before my eyes. About four foot away in fact, it was a small ground. I was soon hooked, and despite all the hardships, setbacks and losses, I will always be a Bankie. AND the support was deliberately and self-consciously non-sectarian, and still is! A good team for an atheist – the Clydeside Reds. 🙂

There is SO much I want to talk to you about in the above piece, but I won’t do so now, hopefully we can catch up for a chat sometime soon. We’ve a fair bit of catching up to do.

Derek.

admin · at

Hi Derek, thanks for your kind comments and nice to hear from you after all these years. I suppose a Clydebank upbringing was a shared journey for many whatever church you practised in. I recall going to Kilbowie on many occasions, though getting a lift over the turnstile stopped when I got to around 12 stones. A good team for an atheist. Love it. Will catch up on messenger. Best wishes, Barra.

Peter · at

Chris, you’re upstairs at my home in Iowa sleeping no doubt until past noon. I just want to say I read this a second time a year later than the first glance and it’s wonderful when read more closely. The story of your dad and mum and siblings lost and present is done with such a sensitive touch and lack of embellishment, wonder how you developed your talent for writing. It’s a slendid piece and I rather feel a bit like a family member after reading it.

Globe Trotsky · at

Peter, thanks for taking us into your home and your hospitality, comrade. I appreciate anyone who takes the time to read this story. I always consider myself a journeyman wordsmith; so any words of encouragement will be humbly accepted. I just hope I did my dad proud with the story. And \i’d love to return your hopsitality in London if you ever fancy a visit.