Cheat or superhero, Maradona or Diego, addict or athlete, first or second goal against England? Your answers reveal much about your personal politics and outlook according to Globe Trotsky following the sudden death of the Argentinian icon.

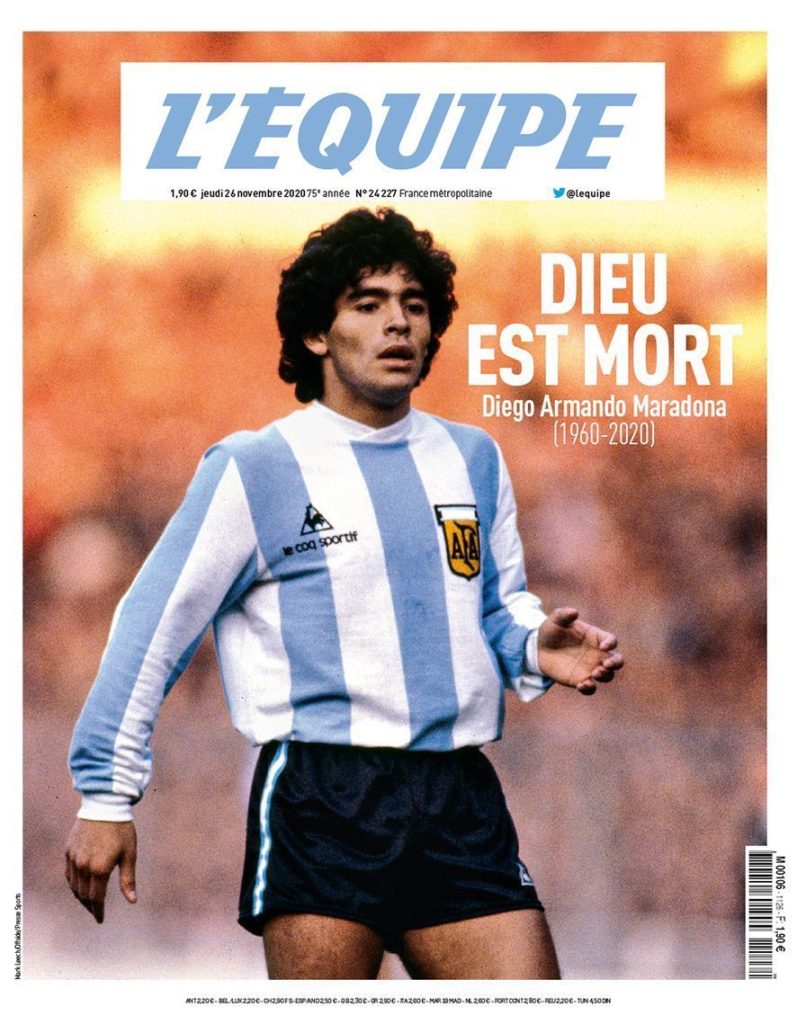

What more is there to be said after the outpouring of public grief to the sudden death of footballing superhero Diego Maradona last week.

Writers more eloquent than me have already had their say. And everyone knows the contours of his story.

But as a Scot living in England who saw Diego Maradona play it was interesting to pick through the bones of the reaction to his death and assess legacy he leaves.

I must admit to being binary about most things; football is no different. Celtic and Rangers, Labour and Tory, rich and poor. Did I mention Scotland and England? The wee guy versus the establishment.

Diego fits snugly into my paradigm.

Socio-economic underdog

As a Celtic fan, the socio-economic underdog has been a feature of football politics my whole life. Rangers were the establishment club; richer, with a bigger fan base and supporter in high places.

Celtic were the upstarts, formed by poor immigrants and their success sticking in the craw of those who saw a natural order of superiority being upset. Hubris and entitlement encapsulated in their Rangers supporters’ mantra: “We Are The People”.

Diego Armando Maradona (possible a Catholic name) was – like many of the greats for me, such as Pele – the ultimate street fighting footballer. Honing his incredible skills in the back streets of Buenos Aires slums, he was destined to be a savior for his family, his nation and a fighter for his type of people: poor people.

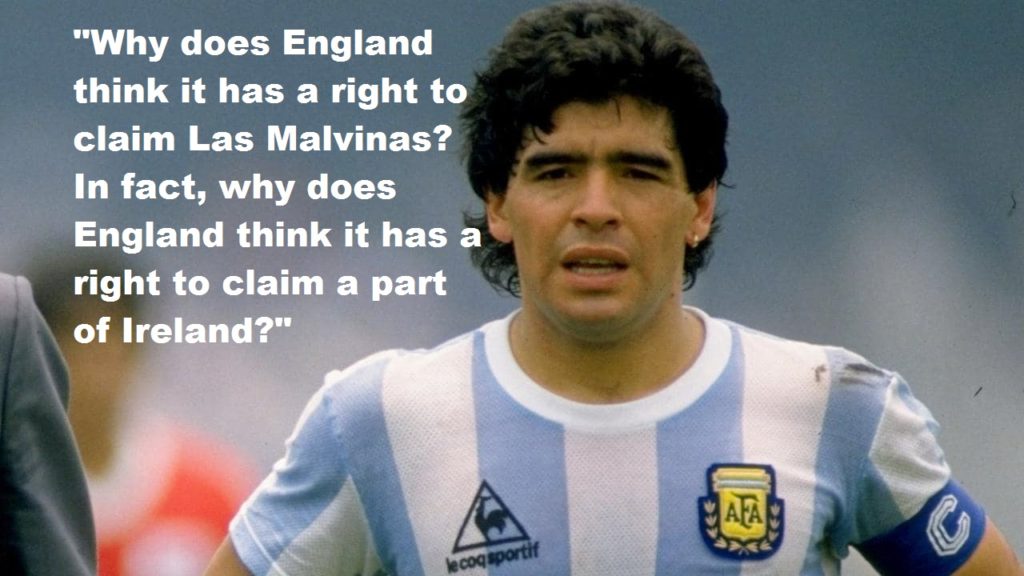

Like much of his footballing headlines there was a wider political metaphor. His goals to defeat England in ’86 came just a few years after the Falklands War. And his arrival in Napoli saw the poor country relations in the south stick two fingers up to the northern metropolitan elites of Milan and Turin.

This was at a time in the 1980s when Serie A was home to the world’s best footballers and the most prestigious global league. Through Maradona Napoli enjoyed a purple patch against Juventus, on one occasion putting six past them.

“There was the sense the South couldn’t beat the North,” Diego said. “We played Juventus in Turin and scored six. Do you know what it means when a club from the South puts six past Agnelli!”

Juve, the Italian club with the most silverware, is owned by the Agnelli family, the capitalist owners of the what was the FIAT motor company. For the average Neapolitan, for most Southerners, beating Juve meant the south beating the north, which also translated as the poor beating the rich.

It was a similar feeling when Maradona helped Napoli to the 1989-90 title defeating AC Milan, the club owned by a upcoming captain of Italian capitalist industry, Silvio Berlusconi.

Scoring for Social justice

He pointedly defied the Napoli’s president’s refusal to arrange a charity match for a sick child to pay for a vital operation. Organising the match on a muddy pitch, he and his team mates got changed in the car park among the cars and mopeds and raised 20 million lire. “I want to become the ideal for poor kids in Naples,” he said, “because they’re just like I was in Buenos Aires.”

It’s the type of working-class solidarity that football embraces and epitomizes. Individual effort and brilliance for the greater glory of the team. It’s no surprise Maradona used his platform to promote social justice long after his playing days were over.

He turned from social justice to political activism when he hung up his boots.

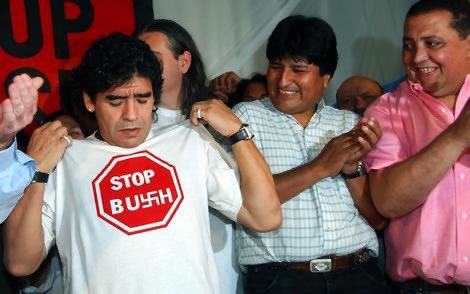

When Argentina hosted the Summit of the Americas in 2005, Maradona participated in a counter-summit along with Evo Morales of Bolivia and Hugo Chávez of Venezuela.

It succeeded in challenging a US push to capture raw materials from the region with Maradona admitting, “I am completely left-wing,” propelling him as an icon of anti-imperialism against US bullying and wider injustice in the region.

He never hid his politics. He saw Latin America’s leftist leaders as his allies. “There is no other Chavez, just as there is no other Fidel Castro or another Lula,” Maradona had said once.

Che Guevara is one of his heroes and he sports a large tattoo of the Cuban revolutionary. He became friends with Fidel Castro following visits to the island to treat his addiction issues.

Unlike other football greats like Pele or Platini, Maradona refused to accept the 30 shillings and has accused FIFA of being a mafia.

Hand of god

Peter Shilton, against whom, the hand of god goal was scored, set the domestic tone with an unpleasant tweet pointing out you can’t cheat death. It came across as sour grapes akin to accusing Pele of erectile dysfunction.

But Maradona’s legacy won’t be shaped by any narrow British or English lens. One moment of outrageous cheating won’t cloud his status as a footballing legend.

Anyone who counts goals and medals misses the point of Maradona. His legacy is as a sporting and cultural icon.

It was doing his job where Diego excelled. On the pitch where he did his talking, and off the pitch where he made his media profile count.

Leaving a legacy

The game is adored in Latin American and has been a ticket out of poverty since it arrived from Europe and notable England in the 1800s. In a continent drenched in the blood of colonization, slavery and exploitation, no other continent has produced so many gifted footballers to grace the beautiful game.

Football has given hope and escapism from the slog of daily life, the alienation of capitalism.

Maradona, with his play and vocal support, represented his class and his culture. He never forgot where he came from and in winning the world cup brought kudos and happiness to a part of the world where global recognition is rarely enjoyed.

Sure, he had an addicted personality, along so many geniuses who have internal conflicts. Like George Best who died and the same day and coincidently, Castro.

In his last interview, given to the Argentine newspaper El Clarin on October 30, when he turned 60, Maradona pondered if he “would be loved” after he was gone.

The overweight, cigar-smoking image of Maradona will fade as will the ‘cheat’ label. Maradona scored his first senior international goal in a 3–1 win against Scotland in June 1979 before going on to enliven the lives of all who witnesssed his craft; his determination and his grace.

Nowhere was Diego happier than on the pitch, where he had a date with his true love: the ball.

It will be Diego, the superhero, the scorer of the second goal against England whose young image will be immortalized in the annals of football and cultural history.

2 Comments

tim64w · at

Re. Maradona’s comments about ‘Las Malvinas’. I’m sure his political instincts would have led him to be be opposed to Margaret Thatcher on just about everything. Yet whoever should/shouldn’t have a right to these islands, Argentina in April 1982 was in the hands of a brutal, right-wing dictatorship and fascist junta, led by General Galtieri, in which many people opposed to the regime just vanished ( a theme of U2 – Mothers of the disappeared, from The Joshua Tree album ). I presume ( hope ) he spoke out against this ?

admin · at

I agree Tim. I think he would would have instinctively opposed the UK under Thatcher, but Argentine politics have always been a bit of a basket case.